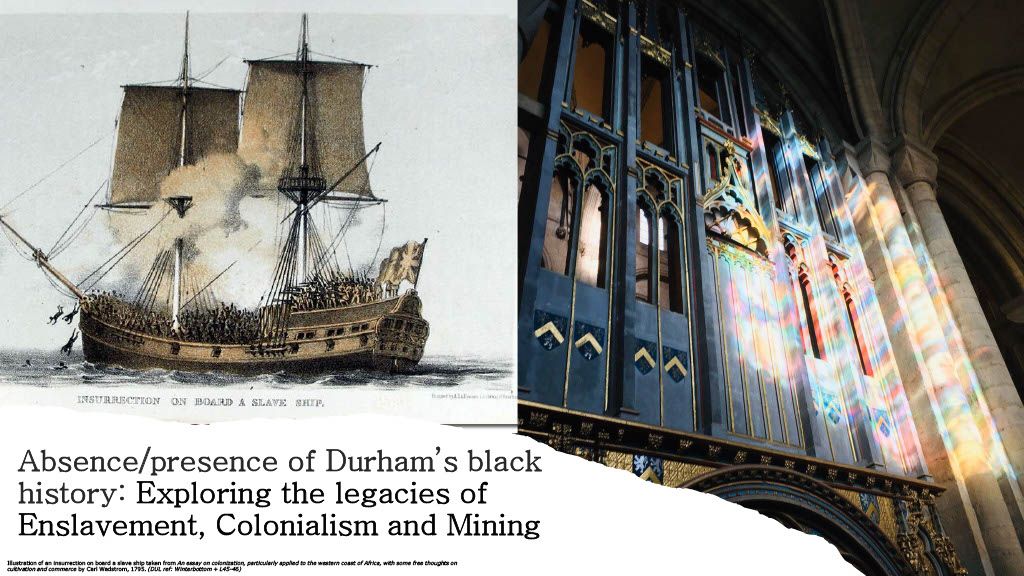

The project owes much to the late community historian Sean Creighton (17 July 1947-15 May 2024) who worked extensively on Black British history and the history of slavery and abolition in the North-East. He was also involved in the Tyne & Wear Remembering Slavery project in 2007 and the North-East Popular Politics Project in 2010-13. He maintained a blog on History and Social Action. In addition, he co-led history of enslavement walks for students on the Violence and Memory module with colleagues from the Department of Anthropology. He was also a speaker for past Black History Month events for Durham University. Sean has provided valuable inputs to the University's Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism project led by archivist Dr Jonathan Bush and to this Institute of Advanced Study supported project: Absence/Presence of Durham’s Black history. The project also draws from John Charlton’s scholarly work: Hidden Chains: The Slavery Business and the North-East of England (1600-1865) (2008, Tyne Bridge Publishing). The sources for the information about Durham and the North East range from parish records to the accounts of religious organisations, biographies and autobiographies, family estate papers, wills, newspapers and journals, diaries, across a wide range of archives and specialist libraries in the North East and elsewhere. It also draws on specialist databases particularly the slave compensation records analysed by the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership [Legacies of British Slavery (ucl.ac.uk)] at University College London.

It is from these legacies of collaborative teaching and research that this project has arisen. In investigating the ‘absent presences’, of Durham’s black history it is important to move beyond the simplistic and self-congratulatory narratives of the region’s involvement in Abolitionism to focus on the more complex nature of the North East’s industrial ties to slave trade. As we know, on 28 August 1833, the British Parliament passed a legislation that abolished slavery within the British Empire, emancipating more than 800,000 enslaved Africans. As part of the compromise that helped to secure abolition, the British government agreed a generous compensation package of £20 million to slave-owners for the loss of their ‘property’ (The collection of slavery compensation, 1835-43 | Bank of England). Increasingly, what has come to light is the clergy’s involvement in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG later USPG), a missionary organisation which owned slave plantations and 300 enslaved Africans in Codrington Estate (Barbados). Various Bishops of Durham Cathedral received compensation from the British government.

Reports in the media attest to these connections like the news articles titled:

Revealed: how Church of England’s ties to chattel slavery went to top of hierarchy $18m to be spent on project

Beatings, brandings, suicides: life on plantations owned by Church of England missionary arm

Archbishop of Canterbury reveals ties to slavery and says ancestors were compensated for abolition

This compensation received by the Bishops of Durham Cathedral needs to be understood in the context of their role and power with Durham County. In the 18th century Durham was a small town with perhaps at most 4,000 residents. It had very little industry and was a major ecclesiastical centre for the Diocese and Palatinate County of Durham under the control of the Bishop of Durham. The Church was a largescale landowner with rich resources of lead and coal. The growing mining industry owners in Durham leased land to pay rent and other charges to the Bishops.

The Bishops were very wealthy. They were also politically influential both in the region and nationally and kept their secular powers until 1836. They had the ability to not only mint their own coins and levy taxes. They could also raise an army and establish their own legal court. Because of these princely powers the area that they governed was known as the ‘County Palatine’. The Bishops had their own Palace at Bishop Auckland whose archive, stored in Palace Green Library, is being examined by the Bishop Auckland Project team.

Most of the memorials within the Cathedral are however specifically dedicated to wealthy and powerful people (like bishops, clergy, colonial officials) and organisations. This also includes Ralph Neville who defeated the Scots at the Battle of Neville’s Cross in 1436, and the Durham Light Infantry. Alongside, the cathedral also memorialises the family of the abolitionist Granville Sharp and has two memorials linked to mining. What is worth noting, is that the various links some of the Bishops had to the history enslavement remains unmarked in the Durham Cathedral. This project seeks to bring to the surface the various links between the Bishops, the Cathedral, slavery, abolition, mining, violence and memorialisation while also highlighting the commemorative ‘traces’ of black lives present within the Cathedral and Durham city.

Beyond slavery, we also intend to investigate the University’s historical relationship as a degree-awarding institution to Fourah Bay College (Sierra Leone) and Codrington College (Barbados). In general, we want to avoid reductive discussions of whether this or that historical figure or institution was ‘innocent’ or ‘guilty.’ Instead, we will consider these histories through the concept of the ‘implicated subject’ (Rothberg, 2019).This is a category for thinking about historical responsibility when it comes to systems of injustice in which individuals or institutions were not directly involved but still benefitted from, either through their action or inaction, or wider participation in societies or systems perpetrating injustice. In this sense, it is less a case of looking for the ‘smoking gun’ of pro-slavery sentiment or an abolitionist ‘alibi.’ It is about thinking how individuals and institutions were imbricated in systems of domination and exploitation beyond their stated intentions.

For any feedback and comments please email us at [email protected]